Update: The Best

Invitation of 2026 Just Got Better

FABULOUS MUSICAL ENTERTAINMENT

ANNOUNCED FOR THE UPCOMING MARCH 21 & 22 ALL-CLASSES-INVITED WHEATLEY

WEEKEND EVENT IN PALM SPRINGS, CALIFORNIA

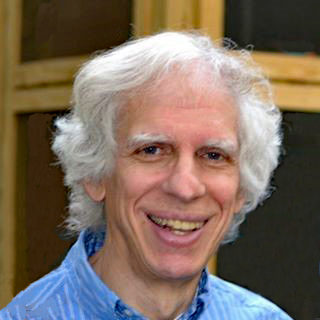

Richard “Rich” Weissman (1972) Writes – “I’m delighted to announce that we will have

spectacular entertainment at the March 21, 2026 evening champagne/wine

dinner. You are all welcome to attend the catered dinner on March 21 at 5:00

pm and the catered poolside lunch on March 22 at 11:00 am, both at our home

in Palm Springs. Spouses, partners, companions, family, and friends are all

invited, and feel free to include those with whom you are travelling or

visiting. Everyone is our guest (my husband, J.D. Horn, and I are picking up

all the costs for both of these events*).

We are now at almost 60

people who have replied “yes” or “maybe” to the weekend events (most are

“yes”). Please pass this onto all those you know from Wheatley. Feel free to

use this as an email blast to your class lists.

If you haven’t RSVP’d (or

if you were a “maybe” and are now a “yes”), email me at rweissman@hotmail.com.

At the dinner, the renowned singer

Nicolas King will perform with his accompanist on the piano. Earlier this month, my husband and I attended Nicolas’

sensational one-man show in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico. His voice is

breathtaking, and we immediately knew that we had to have him perform at the

Wheatley event. We were able to make it work. He comes to our Palm Springs

event from NYC.

Nicolas’ iconic voice has

been on Broadway since he was four years old, with a Broadway career

including Disney’s “Beauty and The Beast,” “A Thousand Clowns,” Carol

Burnett’s “Hollywood Arms,” Sondheim’s “Follies,” “The Wizard of Oz,” and a

multitude of other shows and performances. For ten years (2002 – 2012),

Nicolas toured with his close friend and mentor Liza Minnelli, performing as

her opening act. Nicolas was featured on “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel,” and has

appeared on “The View,” “Today,” and “The Tonight Show.” He has also

performed at Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Cub (London),

Birdland Jazz Club (NYC), 54 Below (NYC), and other venues worldwide.

Nicolas’ accolades

include many coveted awards, including twice winner of the Talent America

Award, Broadway World Award, AMG Heritage Award for Artist of the Year, Mabel

Mercer Foundation Julie Wilson Award, AMG Heritage Award for Artist of the

Year, Bistro Award for Outstanding Performer, and others including

consideration for the Grammy Award for his latest album. He has numerous

albums available on CD’s and major streaming venues. Although young, he

brings the classic Great American Songbook and jazz genres to audiences

worldwide with a voice that is both quintessential for these genres yet

original.

Nicolas today …

Nicolas with

Liza Minnelli performing together …

* You provide

your own air travel, ground travel, and accommodations. Email me if you need

information on places to stay or have any questions.

Richard (Rich) Weissman

Class of 1972 (but

graduated in 1971 and not in the 1972 yearbook)

Attended North Side

School grades 1-6, and then Junior and Senior High at Wheatley

Email: rweissman@hotmail.com

Cell: 503.250.4545

Website: www.richweissman.com

Residences

Palm Springs, CA (Andreas

Hills)

San Francisco, CA (Nob

Hill)

Black Butte Ranch, OR

(Cascade Mountains, Central Oregon)”

A 2022 USA Today Article About Racism on Long Island -

Modified Somewhat from the Original

“Pam’s experience at my 1960s white school is the history we

need to teach. Not ignore.”

“Where

were the adults who should have made sure that we learned about the centuries

of official and unofficial policies that shaped North and South, Pam’s family

and mine?”

Jill Lawrence

More than 50 years ago in

Mississippi, a Black teenager named Pamela Gipson decided to spend her junior

and senior years at a blindingly white high school on Long Island in New

York. She was 15 years old, and she missed home so much that sometimes, she says,

“I would walk down to the street and through the woods to see a major

highway, just to see Black people driving.”

What on earth led her to

leave everything and everyone she knew at that age?

The simple answer is that

her parents wanted her to have an excellent education and a limitless future.

She wanted all that, too. Syosset High was an exceptional school with far

more resources than her segregated high school in Jackson. “The whole idea was

to broaden my horizons, to better myself, to have a better opportunity,” she

says.

Black ‘Exchange’ Students

There were good high

schools closer to home, and a few Black students were starting to attend

white schools in Jackson. But “back then, there were all kinds of dangers for

integration in schools,” Pam says. Rather than subject her and themselves to

those fears, her parents agreed to the safer alternative: Going North. “My

daddy told me years later that my mother cried every day,” Pam says.

I was one of her

classmates, and I just learned all of that this year.

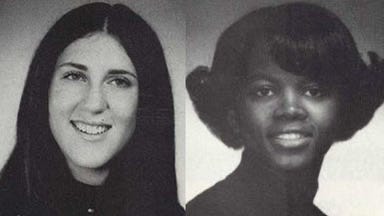

L-R - Jill

Lawrence, Pamela Gipson

When the program was

explained to her, Pam says, “the idea was it should have been an exchange.”

Then, she added what we both knew: “No one ever came from Syosset back to the

Deep South.”

Then, as now, few

Northerners knew much about the South and the Black experience or felt any

need or obligation to learn. Then, as now, the burden was on Pam, and Black

people writ large, to figure out how to adapt, to accommodate, and even

sometimes to survive.

Syosset was like most suburbs on Long Island and across the

United States: almost entirely white. Pam wrote on her 1970 yearbook page

that there were four Black students at Syosset High (one of them another

“exchange” student from the South). There was also a Black art teacher during

our time there, along with a couple of South American exchange students and a

handful of Asian American classmates. One of them was Elaine Chao, who went on to marry Mitch

McConnell, now the Senate Republican leader, and to hold Cabinet posts in two presidential

administrations.

These dashes of diversity

were nearly imperceptible in a school of about 2,200 students. I don’t recall

anyone mentioning the absurdity of Black “exchange” students from our own

country. I don’t remember any teacher or student commenting on the overwhelming

whiteness of our town and schools.

And I didn’t think to

ask, nor did Pam.

I was worried about how

my hair looked, how to end the Vietnam War, how to pass calculus, why girls

had to wear skirts or dresses to school, even when it snowed. I was a

teenager.

And so was Pam, even as

she coped with problems unimaginable to me. She had been an excellent student

in Jackson, but in Syosset, some teachers made her doubt herself. She also

encountered “colorism,” or prejudice triggered by her dark skin. “I questioned

who I was,” she says.

‘The history we forget to remember’

When America started

arguing last year about how and even whether to teach kids about our nation’s

ugly racial history and its seemingly infinite half-life, I started wondering

what had happened to Pam and what she thought about that argument. When I finally

found her, we both marveled at the vacuum in our education. Where were the

adults who should have made sure we learned about the centuries of official

and unofficial policies that shaped North and South, Pam’s family and mine?

Here are a few bits of

history that seem like news flashes, even today:

New York was a slave

state, starting with 11 Black Africans “purchased” by the Dutch

West India Company in 1626. Slavery was especially popular on Long Island

because the area needed labor. Most slave owners on Long Island enslaved just

a handful of people. They worked on farms, in homes and sometimes as tailors,

whalers or other skilled jobs.

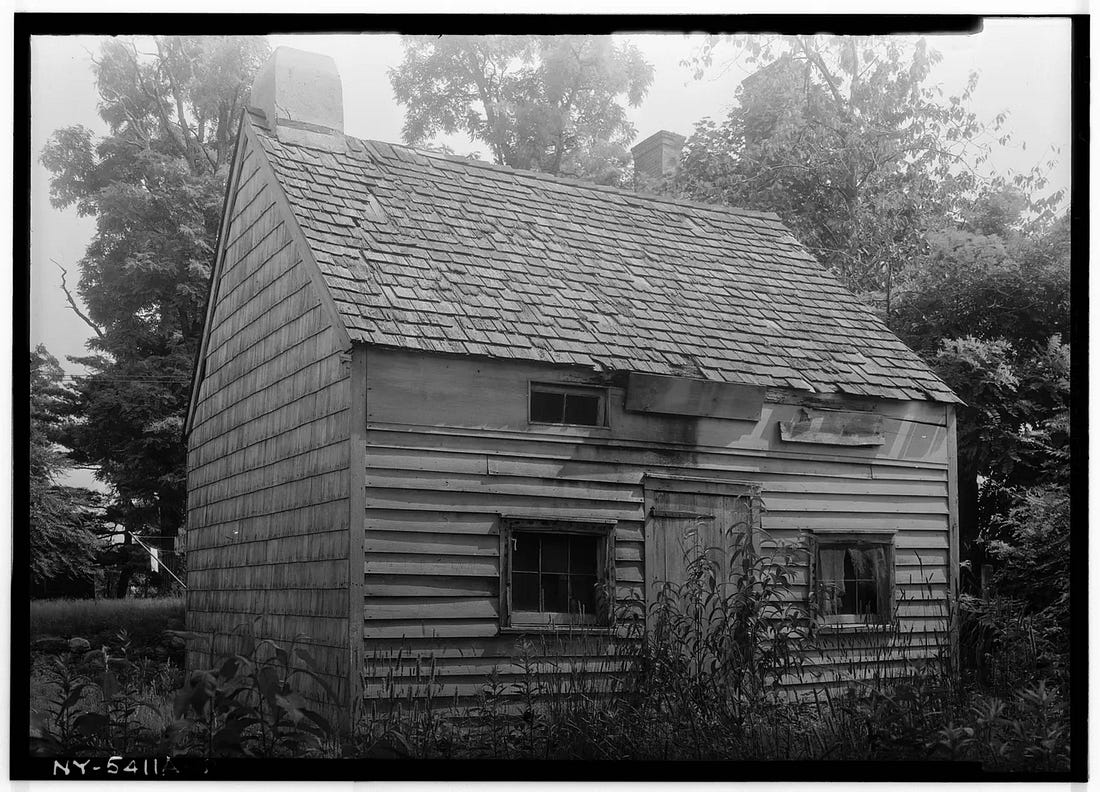

Caleb Smith

Slave House in Commack, NY.

Long Island’s two

counties, known then as Suffolk and Queens (most of today’s Nassau County)

had the highest enslaved population in the North during most of the Colonial

era, according to historian Christopher Claude Verga, author of “Civil Rights on Long Island.” Or, as WSHU

public radio in Westport, Connecticut, put it in 2020, “Slavery was not just

a ‘southern’ thing. It played a central role on Long Island.” The station

called it “the history that we forget to remember.”

Under pressure from

abolitionist Quakers, New York phased out slavery by July 4, 1827. But as

in the South after the Civil War, many freed slaves worked for their former

owners as tenant farmers, and New York cut them out of the political process

with a constitutional amendment requiring property ownership to vote.

This “racial caste

system,” as Verga calls it, was still in place a century later when Long

Island became a hotbed of Ku Klux Klan activity. The historical record

includes jarring documentation of the Klan as a highly visible part of life

on Long Island. KKK members in robes and hoods, their faces fully exposed,

attended funerals, held rallies, sponsored fire department events and marched

in community parades.

Ku Klux Klans

women turn out for a parade in Lynbrook, NY on July 20, 1930

Ku Klux Klansmen

in Freeport, NY march beside a fellow KKK member’s hearse.

This, too, like slavery,

was not just “a ‘southern’ thing.”

During the 1920s, as it

grew more Catholic, Jewish and Black, Long Island had the largest Klan

membership in New York, and the Klan had “a strong presence on most of Long

Island” until the late 1970s, according to Verga. Klan members “infiltrated

local real estate markets and law enforcement and gained political

influence.” Real estate brokers, mortgage bankers and insurance companies

were their “financial backbone,” Verga wrote.

This unholy

segregationist alliance locked Black people out of the post-World War II

housing boom and white neighborhoods. In Levittown, the archetypal mass-produced suburb that sprang

up after the war and spread quickly across the country, developer William

Levitt rented and sold affordable homes to white families only. They agreed

in their leases and deeds “not to permit the premises to be used or occupied by any person other than members of the Caucasian race,”

except for domestic servants.

It sounds like an outrage

now, but as historian Joshua Ruff wrote in American History magazine, it was

national policy then: The Federal Housing Administration supported “nationwide racial covenants and ‘redlining’

– or devaluing – racially mixed communities.”

Covenants barring Black

or nonwhite residents were common all over the country, including in and

around the Washington, D.C., neighborhood where I live today. In 1930, one

nearby development promoted itself on a billboard as “restricted” (to whites only). Early in the

20th century, the Chevy Chase Land Co. required that no property “shall ever

be sold, leased to or occupied by any person of negro blood.” Except, as in Levittown, your

domestic servants could live in your house.

Billboard for a

whites-only “restricted” home development in 1930 in the Washington, D.C.,

area.

Syosset did not have

explicit covenants. It just had an implicit rule: You do not sell to Black

families. This line was not crossed until 1964, when a white family arranged

a sale to a Black family. Local newspapers chronicled what happened next.

Essentially, nothing.

“For the first time in

Syosset’s history, a Negro has bought a house here. And the skies have not

fallen,” the Syosset Tribune wrote in a June 11, 1964, editorial headlined

“First Negro Here.” Or, as Newsday put it a couple of months later, “A Negro

Family Finds Serenity in Syosset.”

Lost opportunities that still reverberate

It is impossible to

overstate the damage done by governments, banks, developers, realtors and

countless other players in creating segregated residential suburbs all across

America. Though housing discrimination has been illegal for decades, its

legacy is very much present.

In 1997, a Queens College

sociologist found that Nassau County was the most segregated suburban county in America.

That’s where Syosset is located; in 2021, only 0.8% of its population was Black or African American.

“It was the way of the

world,” says Elaine Gross, who founded the Syosset-based group Erase Racism and led it for 21 years before

becoming president emeritus in September. “The official policy was that you

do not mix the races in housing. And one way to ensure that is to have a

policy that says you can’t get a loan if you’re an African American. You will

not be able to get a government-backed mortgage. And you can’t leave the

segregated areas and go to another area.”

These policies have

reverberated through the generations in lost opportunities for Black families to own

homes and build wealth.

My family of commuter

dad, stay-at-home mom and three kids fit comfortably into these exclusionary

suburbs made just for people like us. I was white, privileged and oblivious.

I was cramming two years of high school into one so I could leave town. I had

proposed and won approval for an independent study English project on “Black

male sexuality in literature.” Me, a white teen in an almost entirely white

town. In my defense, reading Eldridge Cleaver truly was educational.

But it never occurred to

me to ask questions about the near total absence of students of color, and

unpleasant close-to-home truths about race did not come up in class in the

1960s. I don’t recall learning about Long Island’s enslaved people, the KKK,

the racial covenants, the iron-fisted segregation, or the role of local and

federal governments in perpetuating a blatantly discriminatory housing

system.

As recently as 2008, in

his book “New York and Slavery: Time To Teach The

Truth,” Alan J. Singer – a professor and high school social studies teacher –

documented the racial history of the North and its absence from New York

classrooms despite the state’s central role. Reviewer William Loren Katz said

the subject “has yet to find its niche in our school social

studies curricula, in teacher college courses, and on Regents examinations.”

A teen ambassador in her own country

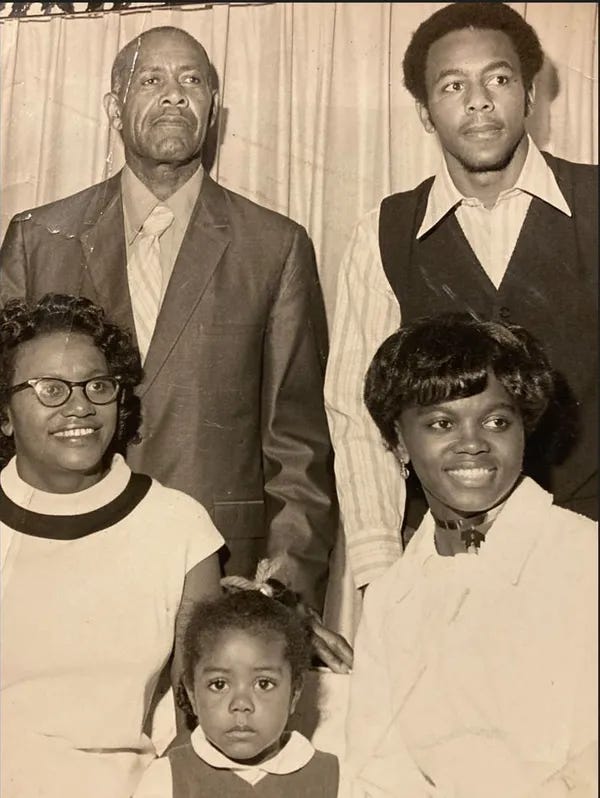

The Gipson

Family in 1972, clockwise from bottom left: Thelma Gipson (Pam’s mother);

Lonnie Gipson (her father); Jeffrey Gipson (her brother, age 17); Pam Gipson

(age 19); and her godsister (age 2).

Pam moved to Syosset in

1968, the same year Congress passed the Fair Housing Act and just four years after

the first Black family had bought a house there. She was surprised by what

she found. Her high school counselor in Jackson and a local Urban League

official had said she’d be living with a family. But, she told me, “I can’t

tell you that they said you’re going to be in an all-white environment. I

don’t remember that coming up.”

Much of what she

encountered in Syosset, however, was sadly predictable. “Many people thought

I came from a large family, and that I didn’t know my father, that we had

dirt floors,” she says. “I said ‘No, I have a mother and a father. They’re

married. I live in a house, and my parents own the house.’ ” And for the

record, she has one sibling, a brother.

Her father, with a

sixth-grade education, drove an 18-wheeler brick truck and rose to brickyard

supervisor. Her mother, who finished high school, was a beautician and a

beauty salon owner. “They were excellent providers. They were active in their

church in leadership roles. Had they not been deprived of opportunities to

advance themselves, they would have been – in my opinion – very outstanding

professional people,” Pam says, laughing as she adds “in my opinion.” We both

knew it was a fact.

Pam’s host family, with

three teenage sons, threw her a party and did all they could to make her

comfortable. “People thought I was a maid. But I was actually a member of

that family,” Pam says.

Pamela Banks and

her Syosset host mother, the late Jane Perlstein, in NYC in 2015.

John Perlstein, one of

her host brothers, says his mother, Jane, was “delighted to have a daughter

in the house” after raising three sons and was fiercely protective of Pam.

Both his parents “made sure that Pam knew they had her back” if she needed

them, he says.

The Perlsteins lived in

Muttontown, a tony area with large homes and lots. My parents, both college

graduates, lived there as well. They had moved from a small 1955 split-level

to a larger Muttontown ranch house in 1968. So Pam and I were neighbors, but our

paths did not cross in a meaningful way until this year.

‘If you open up the door, I’ll show you what

I can do’

My trajectory was not

unusual for that time and town. I went to the University of Michigan,

protested the Vietnam War and wrote for a feminist newspaper in Ann Arbor called

“her-self.” I became exactly what anyone who knew me could have guessed in

junior high school: a politics reporter and, in 2009, after 32 years of

reporting, a columnist.

Pam’s uncharted, far

braver journey continued beyond high school. She probably would have attended

Tougaloo College near Jackson if she hadn’t relocated to Syosset. Instead she

went to Ohio’s Antioch College, which she recalls now as an “almost radical” liberal

arts campus popular with white, well-to-do hippies in T-shirts and torn

jeans.

That was not Pam. She

calls her college self “a Southern belle” who wore dresses and skirts and did

not smoke, drink, protest, go to jail or get arrested. She was not angry. She

was, she says, focused on improving and proving herself: “It’s like James Brown

would say – ‘I don’t want nobody to give me nothing. Open up the door, I’ll

get it myself.’ I had been so used to doors not being open. So my approach

was, if you open up the door I’ll show you what I can do, how I can succeed.”

Antioch’s real-world work

requirements allowed Pam to connect with civil rights and War on Poverty

activities in her home state. She worked with children in the Mississippi

Delta and at the Jackson office of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights

Under Law. The assignments gave her a mission: “I said, ‘I must go back home.

I need to be home trying to help.’ ”

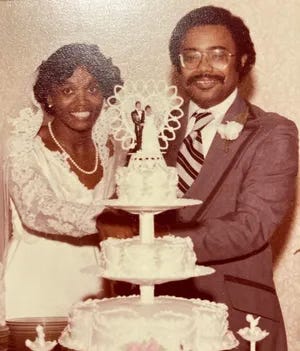

The wedding of

Pamela Gipson and Fred L. Banks, Jr., on January 28, 1978, at Hope Spring

Missionary Baptist Church in Jackson, Mississippi.

On her page in the 1970

Syosset High School yearbook, Pam said she was confused in Syosset about who

she should be. “I am picking up the pieces to my puzzle slowly,” she wrote.

“It is my goal to be me, Pam Gipson, young woman, black soul-sister. I shall succeed.”

And she did.

After graduating from

Antioch, Pamela Gipson earned a masters degree in social work and a Ph.D. in

psychology. Dr. Pamela Gipson Banks is now a licensed clinical psychologist,

a professor and chair of the Department of Psychology at Jackson State

University. She has a daughter, two stepchildren and two grandchildren. Her

husband, Fred L. Banks, a former civil rights lawyer,

state legislator, trial judge, and Mississippi Supreme Court justice, is a

senior partner at Phelps, a large law firm.

Reckonings with racism and treason

Wild pendulum swings on

race have been a constant in America’s past, for centuries and in our

lifetimes. Just in the last couple of decades we have seen police brutality

against Black people and multiracial Black Lives Matter protests and Barack

Obama’s historic election.

A Ku Klux Klan

member in Hampton Bays, Long Island, New York on November 22, 2016

So much of this is

occurring in a historical vacuum for people of all ages. It was 2003 when

Congress passed a bill to establish a National Museum of African American History &

Culture and 2016 when it opened – nearly four centuries after the

first enslaved people set foot in the New World.

The 1968 Fair Housing Act

was supposed to end discrimination in housing. But on Long Island, a Newsday investigation 50 years later showed

that it had not.

Late last year, New York

Gov. Kathy Hochul signed nine new fair housing laws designed to end

statewide the bias exposed by undercover Newsday investigators who secretly

recorded real estate agents and prospective buyers.

Education has also been

resistant to transcending the past. Dr. James F. Redmond, a Syosset schools

superintendent hired in 1963 from New Orleans, is a case study. In a March

1963 profile, the Syosset Tribune said the Louisiana Legislature had fired

Redmond seven times for integrating schools as ordered by the Supreme Court – and a federal

court reinstated him each time.

‘Economics of inequality’

Whatever the exact number

of “firings,” Redmond stood up to the pressure and his

presence in Syosset was a harbinger of later progress. Syosset High School

has worked for years with groups like the Holocaust Memorial and Tolerance

Center and Erase Racism, has relationships with others through a Diversity

and Inclusivity Task Force, and has long offered electives on the “economics of inequality,” “government &

society in the 60s and 70s,” and “contemporary issues in Asia and America”

(the town is now 29% Asian American).

After George Floyd was killed by police in 2020, Syosset school

superintendent Tom Rogers said he had heard from former students wishing that

“their own experience learning about racism at Syosset had been

more thorough.” Since then, the high school has added a full-year Long Island

Studies elective that dives into postwar history, including residential

segregation, and also touches on slavery and the KKK presence on Long Island.

Is Syosset typical?

Gross, of Erase Racism, suggests it is not. “We work with high school

students and they tell us they do not get that history,” she told me before

she retired.

In sessions with

educators, she says, some said they learned new things at an

Erase Racism presentation summarizing 400 years in 20 minutes. “There is a

kind of ignorance about everything,” she says. “We still meet people in our

workshops that don’t even know the story of Levittown and the federal

government’s role in segregation.”

A past that refuses to recede

The Floyd murder

initially had an energizing effect, not just in Syosset but on educators

nationwide. New York state’s Board of Regents captured the mood in April 2021

with a new diversity, equity and inclusion framework

designed to make students feel like they belong and have a voice. The entire

nation has reached a “point of reckoning,” the authors wrote. “Finally, we

appear ready to address our long history of racism and bigotry, and the

corrosive impact they have had on every facet of American life.”

Gross says the New York

curriculum plan spurred some districts to explore how to bring more racial

history and diverse books into their curriculum. “We thought that was really

going to be a bonanza of all things good related to public school education.

And then the school board elections came,” she says, with attacks on CRT,

threats of book bans and fears stoked by outside groups.

At least one group

canceled an Erase Racism workshop “because of this whole topic,” Gross says,

and curriculum discussions on race during the 2021-22 school year largely

moved behind the scenes – if they continued at all.

The risks of not teaching about racism

You only need look at Pam

Gipson’s life to see the risks of not talking and teaching about the facts of

systemic racism.

Residents

distribute cases of water in Jackson, Mississippi on September 3, 2023.

Infrastructure: Jackson’s water crisis isn’t just a moment. It’s a

systemic catastrophe.

Pamela Gipson Banks lives

in Jackson, an 80% Black city where the water system collapsed in August.

That was the culmination of chronic underinvestment in Black communities.

Years ago, Pam left home

for educational opportunities that weren’t available to her then in Jackson.

That was the result of chronic underinvestment in Black schools generally, leading to Black

underrepresentation in higher education, leading in turn to affirmative

action and the Supreme Court arguments Monday on whether Harvard and the

University of North Carolina may continue to consider race as a factor in admissions.

We can push for students

to learn about all this. Or we can perpetuate generations more of ignorance

about how America failed Black families like the Gipsons in ways that are

rooted in yesterday yet persist today.

L-R - Licensed

Clinical Psychologist Pamela G. Banks, a professor at Jackson State

University and chair of its Psychology Department; former Mississippi Supreme

Court Justice Fred L. Banks, Jr.; and their daughter, Gabrielle G. Banks, a

pediatric licensed clinical psychologist, at a wedding in Washington, D.C.,

in 2017.

More than 50 years after

she faced racial stereotyping at a northern high school, Pamela Gipson Banks

says it’s disheartening that “age-old prejudice” is still with us. “I just

feel so discouraged that our advancements have been so limited,” she says. Her

own family has worked toward justice, opportunity and equality for

generations, and it’s not over yet. “We have two grandchildren. We’re

thinking that they might have to make great sacrifices, too. But if they will

help carry the torch, that would be great.”

The triumphant and the

terrible are now part of America’s story. But will it be taught? How much,

and how accurately? The answer is increasingly murky.

Jackson State

University Professor Pamela Banks at the spring, 2022 JSU Commencement

Ceremony in Jackson, Mississippi with her second cousin Symeon Butler (who

received a Master’s Degree) and her first cousin, Donnie Banyard (left) who

received a Golden Diploma marking the 50th Anniversary of his graduation.

Americans with Black skin

have been disadvantaged from the moment formerly enslaved people did not get

the 40 acres and a mule that they were promised, to the moment white

attackers deliberately destroyed Black Wall Street in Tulsa, Oklahoma, more

than 100 years ago, to right now.

Just look at the racial wealth gap (on average, Black

households have 14.5% the assets of white households) and the Black homeownership rate (nearly 30

percentage points lower than whites). Look at the Black incarceration rate, the Black poverty rate, the Black maternal mortality rate – all much

higher.

We are nowhere close to

figuring out how to repair centuries of oppression, generations of potential

unfulfilled. In fact, our collective will to do so may be evaporating. But

our current realities and the history that forged them must be taught. That

is a first step.

So is acknowledging and

celebrating progress and the sacrifices people made along the way. People

like Pam – Dr. Banks – who dared to walk into an unknowable future.

“A big part of this was

to make my parents proud,” she says of her Syosset years. “They were so

devoted to their children, to their community. I didn’t want to do anything

that was going to bring them shame. I was not going to get pregnant or bring

trouble. My folks were just too good to me, just valued me so much.”

Dr. Pamela Gipson Banks

has the life her parents dreamed of for her. As her father used to tell her:

“All that crying your mama did paid off.”

Graduates

1967 - Jack Wolf and Arthur Engoron

L-R - Jackie and

Artie at a pizza joint on East 42nd Street, New York City, on Sunday, January

18, 2026

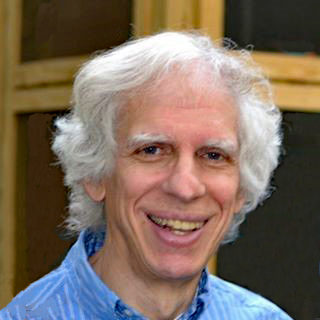

1967 - Art Engoron - I am now working for NAM (National Arbitration and

Mediation) as a, what else?, arbitrator and mediator. I’m honored to join

their roster of legal heavy-hitters who decide (arbitrate) or help settle

(mediate) cases that otherwise likely would need to be litigated (slow,

costly, exasperating). If you submit a case, you can request me (and I would

be tickled pink if you did). NATIONAL ARBITRATION AND MEDIATION

1971 - Dwight Devon - Deceased

Fan Mail

1963 (Mark Friedman) - ❤️

1964 (Richard Ilsley) - ❤️

1965 (Malcolm McNeill) - “Thanks for all you do, Art.”

1967 (Jill Simon Forte) - “Thanks for giving me memories that make me happy … 😊”

1967 (Robert Jacobs) - “Many interesting people passed through Wheatley and

have changed the world! Keep up the good work!”

1967 (Barbara Smith Stanisic) - ❤️

1968 (Barbara Wolowitz) - 👌🏻

1970 (Lyn Goldsmith) - ❤️

1970 (Wendy Strickman Hoffman) - ❤️

1974 (Melanie Artim) - ❤️

???? (“Jon” - Bagdon? Silver?) - ❤️

The Official Notices

All underlined text is a

link-to-a-link or a link-to-an-email-address. Clicking anywhere on underlined

text, and then clicking on the text that pops up will get you to your on-line

destination or will address an email.

The Usual Words of Wisdom

Thanks to our fabulous

Webmaster, Keith Aufhauser (Class of 1963), you can regale

yourself with the first 248 Wheatley School Alumni Association Newsletters

(and much other Wheatley data and arcana) at our website:

The Wheatley School Alumni Association Website

Also thanks to Keith is

our search engine, prominently displayed on our home page: type in a word or

phrase and, wow!, you’ll find every place it exists in all previous

Newsletters and other on-site material.

I edit all submissions,

even material in quotes, for clarity and concision, without any indication

thereof. I cannot and do not vouch for the accuracy of what people tell me,

as TWSAA does not have a New Yorker style fact-checking

department.

We welcome any and all

text and photos relevant to The Wheatley School, 11 Bacon Road, Old Westbury,

NY 11568, and the people who administered, taught, worked, performed, and/or

studied there. Art Engoron, Class of 1967

Closing

That’s it for The Wheatley School

Alumni Association Newsletter # 252. Please send me your autobiography before

someone else sends me your obituary.

Art

Arthur Fredericks Engoron, Class of 1967

Arthur Fredericks Engoron, Class of 1967

ARTENGORON@GMAIL.COM

WWW.WHEATLEYALUMNI.ORG

646-872-4833

Arthur Fredericks Engoron, Class of 1967

Arthur Fredericks Engoron, Class of 1967