Arthur Engoron

April 21, 2025

Dear Wheatley Wildcats and other

Interested Persons,

Welcome to The Wheatley School

Alumni Association Newsletter # 201.

Wheatley Wins Mock

Trial Tournament

After several months of

competition in the Nassau County High School Mock Trial Tournament, sponsored

by The Nassau County Bar Association, The Wheatley School came in 1st

Place, and W.T. Clarke High School (which opened in 1957, one year after

Wheatley) came in 2nd Place. A Mock Trial Awards Dinner will be held on

Thursday, May 15, 2025. [[[I managed to wangle myself an invitation to the

Awards Dinner, so expect an illustrated report soon thereafter. Art]]]

Class of 1995

30th-Year Reunion

The Class of 1995's

30th-Year Reunion will be held in NYC on Friday, June 13th, 2025. For more

information, please email wheatleyrsvp@gmail.com. Peter Krasny

Faculty - Edward

Ouchi Reconsidered

[[[See the comments of

Todd Strasser (1968) below]]]

Wildcat Football

Follow-Ups

Ed Roman (1961) Writes - “Art, I want to clarify a bit about the 1961 football

team backfield. Not mentioned previously is that Chuck

Shaffer (1961) was the team quarterback, at least as I

remember from some 64 years ago. Bob Manniello (1961) was, indeed,

the fullback, and Roger Sullivan (1961), Charlie Hill (1961),

and, I believe, Bob Murphy (1963) were the

halfbacks. I’m lways open to be corrected, as after eighty plus years, things

get cloudier every day.”

Paul Giarmo (1976) Writes to John

“Monk” Moncure (1960) - “Thanks,

John!! BTW, I know what you were doing on Monday, October 27th, 1958. You

were busy blocking a Levittown Division kick that end Pete Krumpe scooped up

and raced 35 yards,’ according to ‘Newsday,’ Tuesday, October 28th, 1958

edition (page 23c). Great 👍 work! You guys beat up those Blue Dragons 32-0 that

day. Go Wildcats!

Paul ("Spirit of

'76") Giarmo

Wildcat Football -

The End?

Paul Giarmo (1976) Writes - I read with interest the comments made by Adam

Goldstein (1980) in Newsletter # 199 about the 1979

Wheatley football team, and he is correct that that team

finished with a final record of 5 wins and 3 losses.

Adam is also correct in

stating that this was the last Wildcat team with a winning record, although I

would give an Honorable Mention to the 1987 team, which compiled a 3 win, 3

loss, 1 tie record. And we all know what happened 4 years later when the j.v.

squad, the last team in Wheatley history, was disbanded on Friday, October

13th, 1991. (Friday the 13th, appropriately enough).

The 1979 team’s three

losses were all by eight points or fewer; against Horace Mann H.S. from the

Bronx by 8, against Jericho by 8, and against the Roslyn Bulldogs by 7

points.

Had the 1979 gridiron 🏈 greats gone

undefeated that season, there's no telling how much more interest would have

been generated in the football program at Wheatley, but history is history,

and once again the Soccer Lobby won out and no football game was played again

at Wheatley for 20 years, until September 24th, 2010, when the combined Carle

Place/Wheatley WildFrog team took to the field and lost to perennial football

powerhouse Plainedge Red Devils, (both varsity and junior varsity teams).

Both the 1979 and 1987

Wheatley football teams deserve to be recognized by the school district, as

well as the 1956 through 1963 teams, all of which had winning records. Just

sayin'.”

Paul ("Spirit of ’76")

Giarmo

Graduates

1965 - Ron Judkoff Writes - “To Dig

a Water Well in West Africa

My Peace Corps Story, Part 1

Peace Corps - Senegal 1971-72 and

Burkina Faso 1972-73

First Trip to Ibel

I’m on a moped about 5

clicks west of Kedougou, Senegal. I’m going just fast enough to stay ahead of

the tsetse flies, but slow enough to avoid snakes that sometimes slither

suddenly across the road in front of me. In my pocket is a spark plug wrench

and a small thin file so that I can quickly clean the plug if it clogs. I

wear a nylon wind shirt despite the heat as slight protection against the

cloud of tsetses that swarm whenever I have to clean the plug. I hear the

telltale p’pop’pop and I stop to clean the plug. My own trailing dust cloud

catches up to me. I pedal the moped to fire the engine for the remaining 15

kilometers to the village of Ibel, where I am to meet with the Chief and

village elders to discuss digging a water well there. I have obtained an

Oxfam grant administered by the good wives of the American Embassy, 800

kilometers northwest in Dakar, to buy tools and materials. This was all done

via snail mail. It’s 1971, and there is no Internet, no mobile telephones, no

outside contact whatsoever except for a four-seat mail plane that comes once

a week…sometimes. There is advantage to this slow pace…African time. I have

adapted, to the heat, the microbes, the food, the water. In the 6 months

since I arrived in-country, I have been frequently ill, but not recently. I

am evolving from a helpless “toubab” into a peace corps volunteer who might

actually be capable of accomplishing something worthwhile.

There is head-high grass

on both sides of the narrow dirt road. I see something ahead, a dead

porcupine. The quills are valued by the villagers for decorations, so without

thinking, I stop to retrieve some quills. I take the machete from the

scabbard I have strapped to the moped to help extract the quills, and I leave

the moped running on its kickstand which, I later think, saves my life. A

leopard had just killed the porcupine when it heard the motor and hid in the

grass. I’m messing with its kill, and this is a seriously pissed-off leopard.

It yowls and leaps over my head from one side of the road to the other. I

stand there stupidly, adrenaline pumping, with the machete held out in front

of me pointing toward where I think it landed. I would be a very easy dinner,

but the engine sound puts it off and it doesn’t come back. ‘Alhamdoulilai.’

In Ibel, I give the

porcupine quills to the Chief, who gives them to his eldest daughter. We

exchange the litany of greetings typical in this part of the world, where

there is no means of news dissemination other than word of mouth. I tell of

my adventure in broken Fulani aided by Samba Wouri Djiallo, who is my

liaison, counterpart, and all-purpose mentor for this project. They think

this very funny. West African bush humor dictates that if no-one died or was

seriously injured, then it’s funny. We drink some ‘dolo’ together from a

gourd bowl that is passed around the circle. I could have used something

stronger. They are sitting gracefully on their heels. I am sitting awkwardly

cross-legged in the dirt, incapable of that very useful position in a world

with little furniture and no sit-down toilets.

We get down to business.

I agree to provide all tools, know-how, and materials. The know-how part is

somewhat questionable, as my total knowledge is from a book I read from the

Volunteers in Technical Assistance (VITA) appropriate technology library on hand-digging

water wells. There is no official Peace Corps water well program in this

remote part of Senegal, but it’s what the locals say they need most. The

chief and elders’ council agree to provide six workers for the digging team.

Six is the minimum number because two people work at the bottom of the well

digging and filling a bucket. The team of four at the top pulls up the bucket

by a rope that goes through a pulley attached to a cross beam. When it is

time to rotate, the four at the top have to pull up the people from the

bottom. Providing a team of six workers is no small decision for the council.

The village lives very close to the caloric intake balance point, so the rest

of the village has to provide extra food for the digging team to make up for

their extra energy output and their absence from working the fields. After

considerable talk and more ‘dolo,’ the council approves. Samba Wouri is

really happy to be getting a water well in his village. He is the brother of

Yoro Djiallo, my Fulani teacher in Dakar during training. Yoro was the

smartest kid in his village school, which got him a free ride to the regional

school, where he was the smartest kid, and so on all the way to the

University of Dakar, where he earns extra cash as a Peace Corps trainer. Yoro

eventually landed a position with the Bank of America in California, but

Samba Wouri remained in the village with a dream to make life there better.

Stealing a Jeep for a Higher

Purpose

I am in Dakar, where I

have hired a truck to carry cement, steel reinforcement rod, and tools to

Kedougou. I will be needing some kind of transport to get material back and

forth between Kedougou and Ibel. During my three-month training in Dakar, I

noticed two identical defunct 1963 CJ-3b ¼ ton Jeeps back behind the Peace

Corps Office. Moustaf is the mechanic and handyman who handles maintenance

for the Peace Corps Office. I give Moustaf a hand with his chores whenever I

can, and eventually he helps me cannibalize one of the jeeps to re-build the

other. Moustaf is a whiz at welding and machining and I can… well… read the

weathered Jeep repair manual that I found. We get one of the Jeeps running,

which we keep secret, and I give Moustaf and his wife the biggest gift

possible on a Peace Corps stipend. When it’s time for the transport truck to

leave, I take the Jeep and we’re off to Kedougou. The trip goes smoothly

except for a few scary moments when it looks like the relatively little

ferry, used to get the relatively big and very heavy truck across the Gambia

river at Mako, leans perilously close to the tipping point (photos below).

Water Witching and Dowsing: Where

to Locate the Well

In Ibel, I have to decide

where to put the well. The little VITA booklet has 3 pages on how to locate

wells based on topology, geology, and vegetation. It doesn’t inspire

confidence. What if we put a lot of effort into a dry hole? It’s a big

investment for the village. Will I be blamed? I have an idea. I pick several

spots that look good according to the VITA book, then I ask the chief to make

the final selection among the spots. He asks the village gris-gris man

(shaman) to make the final selection. The shaman choses the spot closest to

his house, which is also close to the Chief’s house. I’m at least partially

off the hook. We begin.

I pound a small piece of

re-rod into the ground and measure out a meter of string, which I tie to the

rod. I then trace a one-meter radius circle in the dirt with a stick tied to

the other end of the string. Samba Wouri has cut a sturdy looking limb from a

tree, long enough to span the hole. Our lives will depend on its strength, so

I bridge it across two large rocks and we all jump on it simultaneously. It

holds, so we erect the two vertical forked pieces that will hold the cross

piece above the hole. I check the pulley brought from Dakar. Our lives will

also depend on the little piece of metal that is the axis for the pulley

wheel. We hang it from a tree, thread the rope through the pulley, and three

of us hang and bounce on it. The pulley and the rope feel sound, so I

carefully secure the pulley on the cross beam in the very center of the

circle that I drew. The rope will now also serve as a kind of plumb bob so

that we dig vertically as the hole gets deeper.

Americans on the Moon

It is 10 weeks later and

we have finished the well. It is approximately 10 meters deep, concrete

lined, and we have all gotten too casual about riding the rope up and down to

the bottom. The well is yielding plenty of water and life in the village is

about to change radically. Women who used to walk several miles each way to a

seep with heavy clay jugs balanced on their heads now have extra time to

start vegetable gardens. Water which used to be preserved exclusively for

cooking and drinking can now be used for personal sanitation and irrigation.

The team of six will have a new profession digging and maintaining wells.

It is dark and we are

relaxing under a full moon after dinner. Earlier in the day, we had a

ceremony when we finished the protective surface wall around the well

perimeter. We each wrote our names with our fingers in the wet cement of the

wall. Samba Wouri helps those who can’t write. “Ce puit etait fait par…”

(This well was made by…). We stare up at the huge moon. Samba Wouri had heard

that Americans had gone to the moon. ‘What did they find there?, he asks. I

answered, ‘Just dry dirt and rocks and nothing growing.’ Samba sat for a

minute, looked around (it is dry season), and said, ‘Why did they go there;

the could’ve come here?,’ and then after some more reflection, ‘It was

probably easier for them to go there.’ We all nod in agreement.

Afterword

‘Awaale Jam.’ I joined

the Peace Corps during the Vietnam war because I wanted to serve my country

by helping people. My experience in the Peace Corps was eye-opening. I was

immersed in a new culture, and I was able to gain a much more visceral

understanding of how a large portion of the world's population lives. I'm

proud and grateful for the positive changes I was able to bring to the

communities I served, sinking 40 water wells and building baby-birthing

clinics and latrines. I became close to the people with whom I worked. When

your life depends on those at the top of the well pulling you up on a rope

from a 35'+ deep hole in the ground...you get close. We communicated in

Fulani, Wolof, Mossi, and French. My only regret is that the technologies

that allow today’s volunteers to continue their relationships long after

leaving their villages did not exist in the early 1970s. I especially miss

the DJiallo and Ba families. Most of the people I met could not read or

write, so even snail-mail was not an option. A couple of years after I left

Peace Corps, Samba Wouri did write me a recommendation letter through Pere

Pelcot, a French Catholic priest in Kedougou, helping my admission to the

Columbia University Graduate Architecture Program. In a way, my Peace Corps

service set the direction for my life. The cultural sensitivity I gained

served me well throughout my career at the National Renewable Energy

Laboratory, which involved, in part, designing naturally conditioned building

projects in Bamako and Marrakech and leading multi-national International

Energy Agency research projects on energy efficiency and solar energy. To the

wonderful people who allowed me to become a part of their lives, I say

‘njaaraama.’ You had a profound influence on the person I became.

Oh…I almost forgot, I

parked the Jeep where it had been, behind the Peace Corps office, gave the

key to Moustaf, headed to Burkina Faso (where there was an active water well

program) for another 18 months to dig more wells, cashed in my ticket home,

and hitched a ride with some ethno-musicologists bound for the Sahara Desert.

But don’t get me started, that’s a whole other story.

Ron Judkoff, FASHRAE

Chief Architectural

Engineer, Emeritus

Center for Building

Science

National Renewable Energy

Laboratory

12/8/2024

Photo by Ron

Judkoff of the completed water well in the Village of Ibel

Ron Writes - This photo by

Mary Hewson shows us

raising 1/3 of a Concrete Mold near Sabce, Burkina Faso. I was slow to learn

that local clothing is a solar radiation shield and thus the cooler option

Looking south over Ibel

Village.

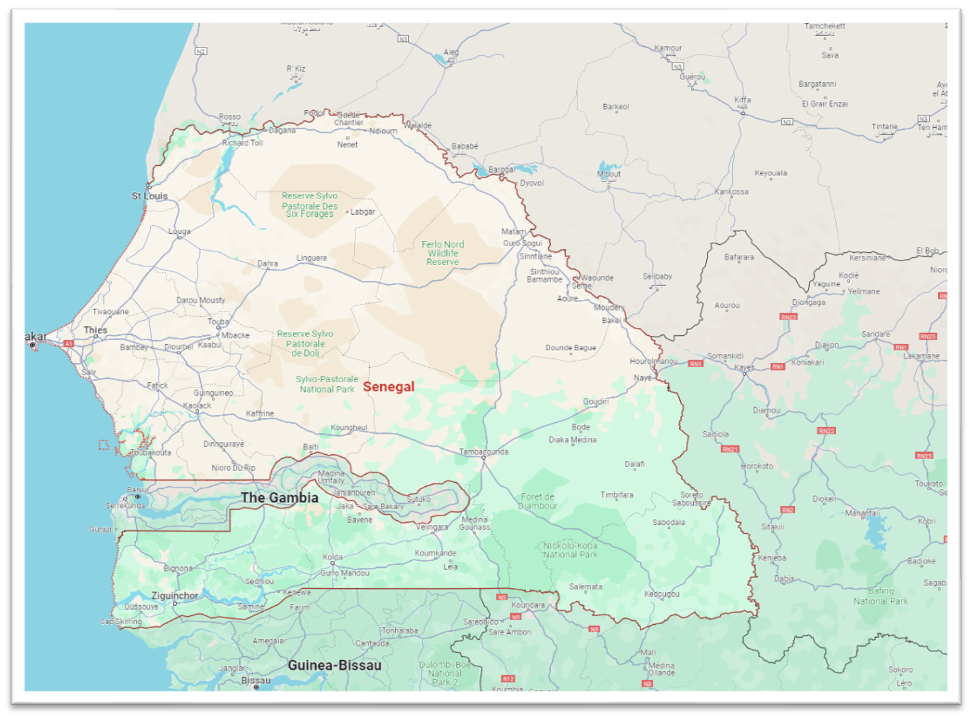

Map of the area.

Photo by Ron

Judkoff, who was holding his breath, as truck and ferry leaned precariously

crossing the Gambia River in Mako.

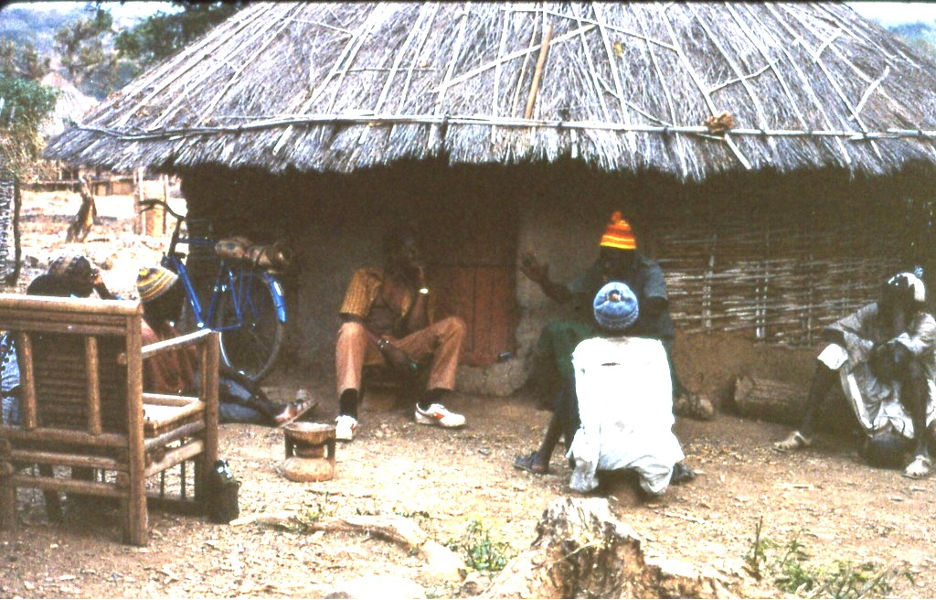

An Internet

photo showing a typical house in Ibel.

1968 - Todd Strasser - Mystery

Novelist

Todd Writes - “A Letter To All The Wheatley Grads Who Were Exposed To

Phonemes:

Like many of you, I am

still suffering from damage to my self-esteem caused by prolonged exposure to

phonemes and other subjects offered at Wheatley in the 1960s. Ever since

those first incomprehensible lessons in Mr. Ouchi’s classroom, I have been

plagued with self-doubt, lack of confidence, and jelly legs. What were these

phoneme things, and how had they invaded our otherwise bucolic Long Island

lives? And how was it possible that there was actually a group of students

(I’m not naming names, but you know who you are) who genuinely understood the

concept? Or at least did a very good job of convincing the rest of us that

they understood it. In retrospect, I now realize that phonemes encapsulated a

significant part of my Wheatley educational experience, which can be summed

up by the single word, ‘mystifying.’

And it wasn’t just

phonemes that made no sense to me. Let’s not forget trigonometry and French.

Please be honest, outside of school, did you know anyone on Long

Island who used trigonometry or spoke French? I sure didn’t. In fact, as a

student, I tended to believe that the only place on Earth where those

subjects (and phonemes, of course) existed was at Wheatley. Furthermore, I

believed that they had been intentionally created by the school for the sole

purpose of separating those students who were capable of comprehending them

from those destined to become World Wrestling Entertainment stars.

True story: As the first

Christmas after high school approached, a friend told me about an amazingly

cheap last-minute ski vacation being offered by the Matterhorn Ski Club: A

$200 round trip plus discounts on lodging and lift tickets. A few weeks

later, we arrived in Zermatt to discover that there was only one thing

missing: Snow. Well, there was some of the white stuff on a nearby glacier,

but you had to take several lifts up, and then take the same lifts back down

when you were finished skiing for the day. We skied for a few days and then

decided we’d probably have more fun spending the rest of the trip in Paris,

from where we would eventually catch the flight back home. It was upon

arriving in Paris that I discovered something absolutely shocking: All those

strange Parisians, with their berets and baguettes, and many clearly too

young or too old to have attended Wheatley, were speaking the exact same

language that I thought Wheatley had made up to separate the wheat from the

chaff. Which could only mean one thing: French had been a real subject!

But, I’m still not sure

about trigonometry.

And as far as phonemes

are concerned? My advice is, fugget about ‘em, or I’ll bodyslam ya.

(Todd has written a new

mystery about baby boomers: “You Can't Hedge Death,” about an unexplained

death in a wealthy Westchester, NY community. It’s available at no cost on

Substack.)

Fan Mail

1965 (Ron Judkoff and Carolyn

Stoloff) (husband and wife) - “We

enjoy the Newsletter, and we appreciate all the work you put into it.”

1965 (Jeff Orling) - “Thanks Art...very much appreciated.”

1972 (Nancy Drummond Davis) - “Thank you for the Wheatley Alumni Newsletter # 200, as

always!”

1975 (David Abeshouse) - “Congrats on publishing The Wheatley School Alumni

Association Newsletter # 200; here’s to 200+ more of them.

I’m looking forward to the 50th reunion of my

class this October – I’m sure many of us are inspired by the Newsletter to

reconnect with our classmates.”

1976 (Paul Giarmo) - “Thanks for all you do.”

1979 (John McDowell) - “Thanks for all you do!”

1980 (Mary Dwyer) - “Thanks for all you do to keep us connected. I know

the Dwyer crew (myself and 5 siblings) appreciate your efforts.”

The Official Notices

All underlined text is a link-to-a-link or a

link-to-an-email-address. Clicking anywhere on underlined text, and then

clicking on the text that pops up, will get you to your on-line destination

or will address an email.

In the first 24 or so

hours after publication, Wheatley Alumni Newsletter # 200 was viewed 2,798

times, was liked 11 times and received one comment. In all, 4,738 email

addresses received Newsletter # 200.

The Usual Words of

Wisdom

Thanks to our fabulous

Webmaster, Keith Aufhauser (Class of 1963), you can regale

yourself with the first 200 Wheatley School Alumni Association Newsletters

(and much other Wheatley data and arcana) at

The Wheatley School Alumni Association Website

Also thanks to Keith is

our search engine, prominently displayed on our home page: type in a word or

phrase and, wow!, you’ll find every place it exists in all previous

Newsletters and other on-site material.

I edit all submissions,

even material in quotes, for clarity and concision, without any indication

thereof. I cannot and do not vouch for the accuracy of what people tell me,

as TWSAA does not have a fact-checking department.

We welcome any and all

text and photos relevant to The Wheatley School, 11 Bacon Road, Old Westbury,

NY 11568, and the people who administered, taught, worked, and/or studied

there. Art Engoron, Class of 1967

Closing

That’s it for The Wheatley School

Alumni Association Newsletter # 201. Please send me your autobiography before

someone else sends me your obituary.

Art

Arthur Fredericks Engoron, Class of 1967

Arthur Fredericks Engoron, Class of 1967